The discussions concerning the establishment of an Institute of Photography, a discussion that is not only being held intensely in Germany but is also flaring up again in Austria, is an occasion for us to seek dialogue with those who are directly affected by this discussion: the photographers. We believe that the situations – also the living situations – are each very individual, furthermore everyone works differently, and that it is worthwhile to establish the difference in the photographic practice and the preparation of the material.

The situation of photographers today is already very different from case to case, and I think it is becoming more and more difficult to justify archives that are fitted into a certain system. There are, for example, these wonderful, very old photographs by Eugène Atget whose work has of course long since been cataloged, just like that of other early photographers. That has long since been done, I suppose. But it is becoming more and more complicated and more and more extensive, especially due to digitalization. I know Juergen Teller, and when he has to take a photo of a bag, he quickly makes 2000 – a friend told me. And one of them is then as he would like to have it. Of course, I don’t know which criterea he uses in the selection and whether he manipulates it further. However, all of this is a way of making pictures today. This alone makes it more and more complicated to create an archive. It’s unbelievable what accumulates when someone takes a lot of pictures.

Now one could say that the other 1999 pictures were not selected by Juergen Teller, but he rather just chose this one picture of the bag …

Maybe he will throw away all the others!

Exactly. Is it enough to keep this one picture?

Everybody will have their own opinion on this. There are certain people who save everything. When I started, I was shooting analogue. Even then, I took a lot of photographs. And to get invested in that would mean having to see through everything.

What is the case for you? Do you look through everything? Have you already devoted yourself to your archive?

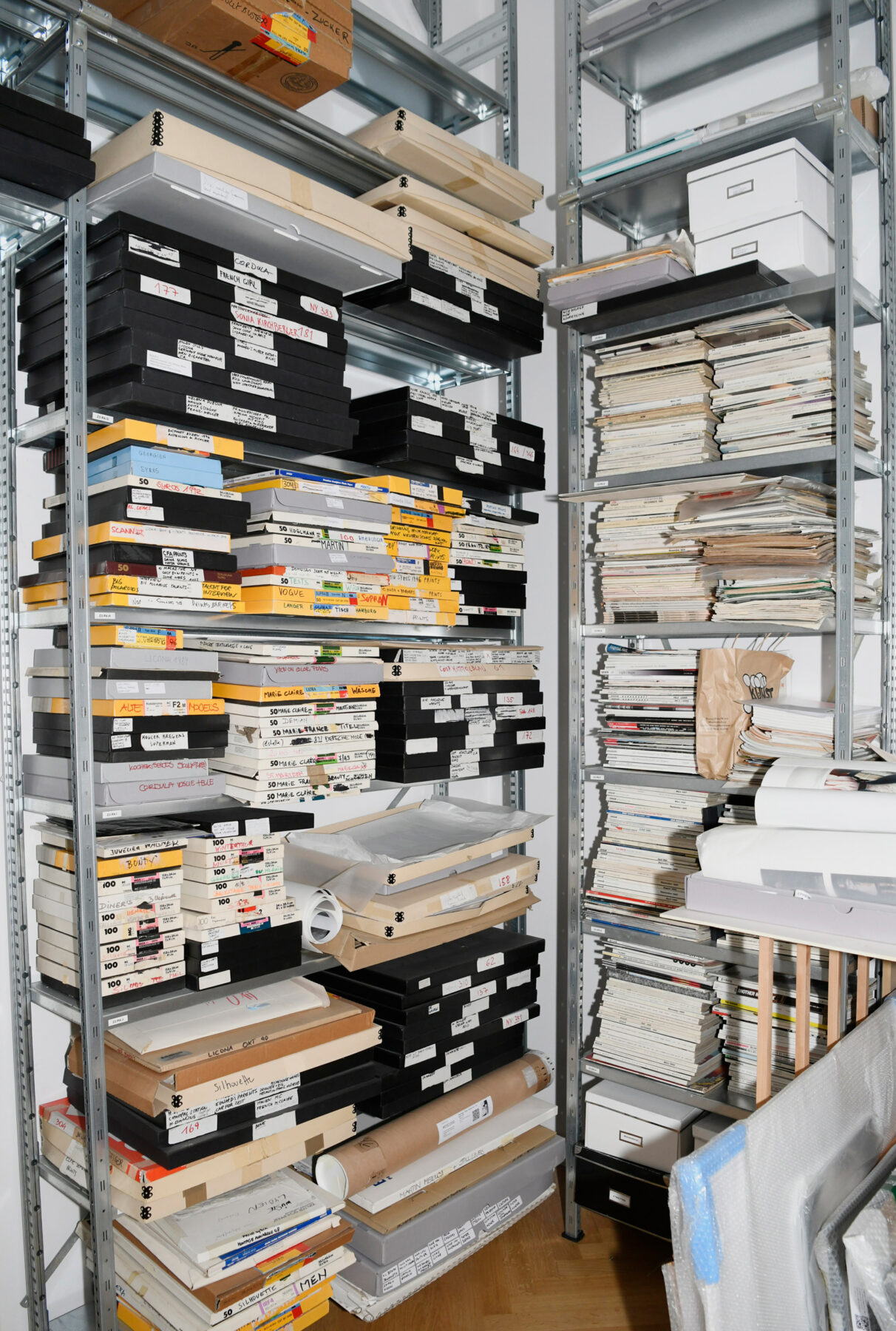

(laughs) So … I have an archive. Everything I took, I developed myself. Except for color, I always had color developed. My sister did the office and always filed and labeled all negatives, contacts and positives in folders, in binders. They were really thick and full. Later, a young woman, who worked here very efficiently, renamed everything. But she actually made a mess, a total mess. At that time, I had no time to spend my time on it. I worked with assistants, but I needed them when I was taking pictures. I didn’t really have anyone to take care of my archive. This wasn’t even common at the time. And even if it had been common, I couldn’t have done it anyway. I was married, had two children. So, that was all complicated. But now, of course, I’m confronted with my archive. I have already started to take care of it a long time ago, at first only mentally. How do I do this now? I know my pictures, of course, because I know how I took them. But what I have done so far in terms of the archive is not enough at all. I’ve made thousands of prints, put the photographs in folders and in files, labeled them, and then put them in drawers. But when I am looking for something, I am going crazy. The various people who enlarged photographs for me when there was something to enlarge would often then take out much more material from the drawer than they needed, and then sorted it back badly. That all causes huge problems. But the biggest problem is: I can’t even take care of my own archive, because then I would have to give up photography. That’s so extremely time-consuming. I can’t do it at all.

Can’t someone else do this archival work, or does it require the photographer’s voice?

I have a wonderful daughter-in-law, Ursula Davila-Villa, who is involved in art, ran a gallery in New York and who said: You have to make an archive. I’ll do your archive, I’ll organize it.

Now that’s an offer you don’t want to turn down …

I sure don’t! Yes, she is doing this. With a lot of energy, but on the side. She is very important for what is done in the archive because she knows how it is done and has an idea of how the work must be done.

Does she “only” tidy up? Or is it also about looking through everything and making decisions like throwing stuff away and so on?

Absolutely. I have always had such a primitive classification system in which one could orientate oneself chronologically or according to the labels or by the labels. These boxes are now organized and you can keep track of everything. This, what we are talking about now … now comes the individual picture, come the details. And that’s just an incredibly tedious work. I have just had a major exhibition at the Kunst Haus Wien.1 That was an occasion to sift through the material. And do you know the Fotohof in Salzburg? Well, they are incredibly qualified. And by the way: If I could decide, I would give them the job of running a museum of photography or institute. Because these people are already doing that, so to speak, and are taking care of archives, with all the trimmings. They came to me and said that we finally have to do an exhibition with photographs that no one has ever seen, with pictures that have not yet been exhibited. I think that’s wonderful. Finally, someone is asking for something other than the well-known pictures. Because everyone always asks for the same ones. Well, and now the guys from Fotohof came and just wanted to have a look at my archive and my prints. I could show them what I have already made, which has already partly been sorted. They were able to have a really good look at some of the things. I’m only telling you this to say that my material is already a bit stored. It’s still a long way from being finished! But one can take something out and look at it. Getting there is incredibly intricate and small-scale work and precious work, precious in each and every aspect, not just money-wise. It’s precious to feel that you have things that are worth seeing. I guess setting up an archive for a painter is much easier because he doesn’t take a hundred pictures a day. But a hundred photographs? Easy.

For way too long, your work has been associated primarily with fashion photography, right?

For a long time, this was the only thing people knew. Nobody looked at my other pictures. But I took a lot along the way, for myself, as another form of my own photographic work. But nobody was interested in that until now.

The curator Daniel Baumann made an exhibition with you in 2006 at Casey Kaplan in New York.2 It seem significant that such an exhibition could take place in the U.S., while here much more self-censorship was still being exercised that art and commission in photography were always dissasociated from each other. So that was more of a European phenomenon and didn’t play a role in the U.S.?

Not at all. In the U.S., no doubts were ever raised about Irving Penn or Richard Avedon.

In the catalog of the exhibition in the Kunst Haus Wien it mentions that the different contexts of your work already come together in that show: art, fashion, commission.

That was the concept I had in mind. I didn’t want a typical retrospective where everything was shown in a logical sequence. I thought I would show the things as I saw them together myself. I pasted something like 300 photographs on the walls in my studio, pictures that I took quite intuitively. And then I gave them to the curators3 to get started. And then, of course, the next step was to clarify what was available in large format or framed, or how the exhibition could be implemented, so that it would be possible in terms of costs, and so on. The director and the curator then loved it just as much as I did; they just threw themselves into it and did the same thing that I had done before and put the pictures together quite freely. This is why the exhibition took a turn that differs from the one you might have expected. But no one noticed my own artistic work for quite a while. Although when I meet a few art directors now, somewhere in New York City, they often say, “But that’s exactly what you did years ago!” And then I ask myself, “Yes, and what were you looking at then?” But of course, that’s also my fault, because I wasn’t able to sell myself. I didn’t have the heart to do so. And I didn’t want to participate in this insanely narcissistic elegance either. At the same time, I was in fashion photography. It was all a challenge for me, that I had to overcome with each commission. How do I achieve that I can do something that I am interested in? How do I achieve that it still somehow works within the scope of the commission? It always worked out somehow. There were people who liked what I was doing, but it was against everything! Against all conventions! Although it wasn’t wild or as eccentric as, say, David LaChapelle. He went even further. With me, it was just a thing that wasn’t clear to everyone. Not before and also afterwards, many didn’t know exactly what they should do with my work now.

Has this world of commissioned photography actually changed? Has more become possible or rather less?

Well, there already is an awareness that the fashion world can definitely be questioned. That it’s not possible to just continue with this cult of beauty. This does not mean that the beautiful and conventional is no longer in demand. But there really is an awareness today and the possibility of doing the job in a different way. It doesn’t happen that often, but if you work with the right people there is the possibility that the work won’t be totally rejected or not understood. There’s someone at Vogue who handles art there, Bernd Skupin. He did an interview with me and said, “It’s only now that I know what you meant five years ago. I didn’t understand it back then.”

This is actually a nice compliment. On the question about the change in the world of commissions, we also interviewed Hans Hansen. Do you know him?

He mainly did advertising, didn’t he? And his student is Annette Kelm. She’s one of the photographers I like the best. Because she presents such special position. And Hans Hansen is such a talented person. Really, he’s doing such a great job. I have nothing at all against advertising. Advertising can be beautiful and intelligent at the same time. It’s just that it’s hardly ever done beautifully and intelligently. He has, however, succeeded in doing so.

Anyways, Hans Hansen told us that the market for advertising, or rather the client mentality, had changed so much that he often no longer had the opportunity to work freely.

Yes, but this is something else. I am talking about fashion photography. I am not talking about advertising, where one practically has no freedom anymore. Everything is exactly calculated and target-oriented. One is no longer looking and waiting to see what works and what doesn’t work. People always know what works, and that’s what they want. And a free interpretation that then works splendidly – and Hans Hensen has certainly made this experience just as I have – no longer exists in advertising today. No one relies on that anymore. People rely on things that can be verified. And these are things that, in my opinion, are not always true. I already saw this in surveys that were conducted in connection with my commissions. Various subjects were shown and people were asked what they liked. And yes, they didn’t like certain pictures. We took them anyway, and suddenly everyone thought they were great. Random people were asked about the pictures, as if they were the experts. Pardon me, but they actually have no idea. They simply couldn’t imagine that a picture could work in a different way. Because they simply had a certain expectation towards pictures and couldn’t imagine that one could also meet a commission in one’s own special way and that one could definitely do something with it.

So, overstepping one’s bounds is what drives you … and with regard to the exhibition, bringing things from different contexts together. Have you always worked like this?

Yes, I have always loved working like that. But I was way ahead of my time with a lot of things. Many people always found the idea very good, but then didn’t really know what to do, where to actually place the work.

If you think of your archive now, would you also put together all the pictures that have been created, whether it’s a free work or a commissioned work? One can categorize, that’s done all the time.

Hmm, good question. I don’t know. I would probably sort the sheet by date and write a corresponding note alongside. From the beginning, I refused to distinguish between art and other work. Because whether something remains or not is decided by time anyway. I didn’t want to categorize there, but that was difficult for me, too. I wasn’t in the situation to say that I’m only doing art now. I did fashion photography and earned money for the family by doing that. But I also enjoyed it. And I’ve always tried to get as far away as possible from a totally commercial, shallow notion of fashion. And also to get away from an image of women as one could imagine they should look like. The American photographer Lee Friedlander, for example, is just great. Somewhere I saw a photograph by him, of television.4 I immediately thought, I’ll take photos now, fashion photographs, with TVs that can be seen somewhere in the picture. The TVs were supposed to be in hotel rooms, in some nice ones – but also in ugly ones. The rooms were supposed to tell of no particular taste at all. And at the same time, I looked at how big the TV had to be or how small it could become. The idea was to make it really small and show fashion in it. I though I’ll see what the reaction is to that. It worked out perfectly. No one complained. Which is interesting, because the TV is apparently such a magic point that anything that’s on it is definitely watched. So that’s great. And of course those were things that were just different and not really in the interest of the fashion industry. If someone asks me today what the television pictures were, then I say of course that that was fashion photography. In my case, it’s probably interesting that the photographs are difficult to classify, because the fashion itself was not as devotedly important as it usually is in fashion series. The fashion itself always appears only en passant in the pictures. The models were wearing the fashion that I had to photograph, but it wasn’t centrally important. What was important were the contexts in which the models found themselves.

You have also portrayed many artistic personalities.

I was married to two artists and have always lived in this environment and decided early on for myself that this is what interests me.

Your portraits of artists also bespeak an equality. One senses the closeness to your respective counterparts and what they stand for. But the question is – also with regard to an archive – where does your work belong to, in the future, institutionally. Margherita Spiluttinis’s premature legacy has now gone to the Architekturzentrum Wien5 – a centre for architecture in Vienna – which in a way makes sense in the light of her oeuvre. Where do you see yourself with your work?

I was just wondering about that too, now that you mention it. After all, I also did a book about architecture, about the conversion of the Landstraßer Hauptstraße, Wien Mitte.6 I love construction sites. I’ve also done fashion photography on construction sites from time to time. But I only photographed at the site as long as it was a construction site. I told the client: when the construction is finished, it no longer interests me. A place interests me only as long as it inspires me intellectually. I find the beginnings and the process interesting. Often, when the architecture is finished, it is depressing. And when it’s time to move in, one often can’t see the architecture anymore.

That means you are working across all genres.

Looks like it. When I accepted the commission for the book about Wien Mitte, I thought, okay, now I’ll have to climb around on all those ladders … and I was also wondering what camera I could use to do that as professionally as possible. And then I thought to myself: no, I do work with a very good camera, of course with a tripod, the light well set, that much is clear. But I’m not striving this perfection and coldness now. That is sometimes beautiful and important. With Hans Hansen, for example, it’s very good. But it also requires a really perfect template. You’re also kind of challenged by technology a bit. Sometimes you adopt positions that are no longer entirely your own. Because then it simply becomes difficult to work differently. Then many things don’t work because the optics are different and so on. That’s where my background of working with artists is interesting. For example, when I photographed Martin [Kippenberger] in 1996 in connection with the work The Raft of the Medusa, I set the light so that it was right for us. The point was to set up the scene in such a way that it didn’t seem artificial. Martin left it all up to me. He just said that it would be nice if we could do something together. And then he also said, maybe you shouldn’t be so precise. And I heard that quite often, mostly from artists who are afraid of this insane precision. Whereby, of course, one has to say: The pictures are very accurate, even if they are not technically accurate.

The artists fear of perfection …

… was not directed at me, but at the medium. In photography, there were times when sharpness was in demand. But there were also times when sharpness was totally frowned upon and blurring was a sign of artistic subversion.

You, for example, mean the Nudes by Thomas Ruff?

No, I mean, much, much earlier works …

You’re looking for a connection to the fine arts, don’t you? Also, when one looks at your book with the architectural photographs of Wien Mitte …

Yes, I have my role models in art history, Bruegel and so on. That allows me to do crazy things. In architectural photography, I like to work with perspectives to turn them into something else. And then also with surfaces or geometries that might look shabby at first glance but are magnificent for that very reason.

Let’s get back to the archive: Do you still have all the material after all? Especially when you think back to the analogue era: Does one not give away originals as well? And do they always come back to one? And how was or is that with copyright in commissioned contexts? Does it lie with you or with the client?

I do not give away my copyright. If you work for a magazine, you have to give away the copyright, but only for one year. Or in other words: One does not give away the copyright, but one can’t use this photograph for other things for a year. And that rarely happens anyway.

And the other question: Is all of your material actually available? Or have some things remained with your clients?

That may have happened here and there, very rarely. But certainly only with things that were not so important to me. I actually have everything together. Once, a whole preview of a new collection by Dolce & Gabbana burned – and there was also a fire at Palmers. But I don’t find that dramatic, because on the one hand I still have similar works, and on the other hand my works for Palmers and Römerquelle have thus become a story about me and my work. It took place in a certain time. Today, I would do this work differently. So okay, well, it would be nice if I still had the original negatives, but part of them were destroyed in the fire.

Let’s go back again to this very personal question: Have you already thought about where your work will find its final place? Or is that a question that doesn’t concern you at all and that your family has to sort out? If you think of the photographer Cora Pongracz, for example: her family gave the estate to the Gabriele Senn Gallery. The work was then indirectly purchased by the OstLicht Collection and comprehensively processed.7 Still, one might ask the question: Why did the museums miss out on taking over Cora Pongracz’s work? Now it is in private hands.

It was always held against me – behind my back – that I am doing fashion photography. And today I also have to say that this disinterest also has something to do with the fact – and I never had this thought my whole life – that I am a woman. Quite simple. And that I have a certain attitude. In my exhibition at the Kunst Haus Wien, there were a great number of visitors. The museum has never had so many visitors, which made me very happy. But of course, I also asked myself the question: Why do certain people not take a closer look? What is it actually about? Many people only know the works for Römerquelle or Palmers. I was known because of this work. I was in fact never not known. And overall I get a lot of affection from people – but I don’t really know why. Because most of them don’t know anything about my work and what else I’ve done in terms of photography. And I must say, the people who matter in our business have always tried to keep me down, despite the fact that I have a gallery or even several galleries. But: I simply tried to do what was important and possible for me from my position as a fashion photographer and what is still important to and possible for me. Many women have always asked me how I manage it with the children. I can only say that it was always important for me to work because I wanted to be independent. And I always thought that you have to work because it’s a fulfillment after all. Of course, it depends on what you do. With the children, it’s not magic, if you earn enough money to afford a nanny. Concerning this, I was always very precise and very constructive. I didn’t want to just superficially discuss but talk about these things in a very realistic way. You also have to feel the need to work and have your own life, to think about things and acquire knowledge, so that you can put this idea into a good shape. That’s just important in the society we are living in. And yes, it’s also complicated. Women are just not relieved from it, they have to take care of it. They always have to think very carefully about what their lives are going to look like if they have children. And I think my clarity and decisiveness about that has helped me.

Great to hear you say that again so clearly.

I have only now found out for myself that this connection exists. Because I have never lacked attention, in a way.

And yet, one can say that the step into an institution did not materialize for a long time. The exhibition at Kunst Haus Wien was, after all, the first solo museum exhibition in Vienna. And furthermore, there is the fact that you temporarily relocated the center of your life to New York. That instills respect, and perhaps one no longer approaches your work with such impartiality.

Yes, of course. Hundertwasser was also completely ignored and really belittled in Austria. For a long time, he was not recognized, but now he is. Slowly the realization is coming that he actually was a very interesting painter after all. And that’s also because he was very business-minded and immediately understood what he had to do to make it work. But this financial skill had no influence on what he did. He invested the first money he made in a film, not bad. But the fact that he dared to invest his money in new projects was resented.

Mixing art and capital so aggressively at that time was probably not seen as a good idea. In your case, of course, there was also the fact that the medium of photography had not arrived in art institutions until well into the 1990s. It’s quite conceivable that the larger museums in particular were a bit reserved about your work.

Absolutely. Only – as I said – if it was at a level like Irving Penn or Richard Avedon, if the work was at the very top, then there were no problems. Both of them have always worked at the very top, in the U.S. So there was never a flaw in the fact that all of these photographers also made fashion throughout their lives. In Austria, of course, there was a Jewish-supported photography before the Second World War. In Czechoslovakia it was even more pronounced, this must be further processed and the connections must be seen.

Meaning, you see the necessity to do something, in particular for the medium of photography, and to explore it further. Do you also see the need to establish a photography museum in Austria?

That is very important. And the Fotohof, of the many institutions that already exist in Austria and that take care of photography, is simply incredibly qualified. These are the ones that completely fulfill the program – that is, everything it takes: exhibitions, publications, archives. But since all these tasks always remain a question of money, they only make the spectrum as large as they can. And that is small. We have to take a better look at what is available in the world and in Europe. There could be two institutions. One takes care of archiving and the other takes care of working out standards for dealing with the restoration of prints that are broken. Basically, of course, it would be better if everything was together. Because similar questions that one is confronted with certainly arise regarding all estates. But it is important to understand that photography is also a part of art. For this reason alone, one is forced to deal more with photography and its technique. After all, it overlaps with other art as well. Photography is an inspiration for many artists, which they integrate into their work today and with which their work is changed. And that, after all, affects the conservation and preservation. Even in painting, it’s no longer just the expensive and complicated and high-quality materials that are used. Beautiful linen behind glass, durable backgrounds, precious colors … that has changed. One uses crumpled papers that are swept into a corner and have to lie there exactly like that. How do you deal with that now? How does it work? I think preservation has become very precious. Because everything has become so fragile. That’s why preservation today replaces the use of precious material. Because art today has just this function that it has now. That’s why preservation is becoming more and more important. After all, in our fast-moving age, resources for art and for exhibitions are becoming increasingly scarce, unfortunately. If you don’t have an archive that allows access to a work without complications, then there is a greater chance that a work will not be seen. Then it is gone. Unless you’re lucky and you’re a guy like Miroslav Tichý, who was deranged, who went everywhere and had an obsession, that carried him all over the place … then you can get away with it, but otherwise? Not so much.

Perhaps not only archives are important, but related to that also material research. A digital photograph taken 20 years ago probably looks different from a digital picture taken today.

Totally. There are worlds between them. Of course, Helmut Newton made beautiful prints, they were very graphic, with beautiful contrasts in black and white. I also knew works from Leni Riefenstahl, these classic-looking figures, athletes and so on. Then when I saw her work in Los Angeles in the original, I found that the prints were all small and coarse grained. That’s when I was completely blown away because I realized how fast the development was going. I hadn’t thought about it until then because, of course, we don’t have originals in our hands all the time. It’s really interesting. The Americans delivered an incredible quality very early on, very special, color photography as well, William Eggleston and so on. There’s just been happening a lot and the quality has improved incredibly. I always thought I could tell right away if a black and white print was digital or analogue. At the MoMA in New York, there was a photography exhibition with pictures by Robert Mapplethorpe, who really made great prints. In one cabinet, there were maybe 60 prints, analogue and digital, mixed, originals and re-prints. I thought: No problem for me, I’ll find out immediately which pictures are analogue and which are digital. I didn’t. I was wrong.

In 2010, there was an exhibition at the Galerie Buchholz in which Wolfang Tillmans showed his first digital prints, mixed with analogue ones.8 There were many photographers in the exhibition who were looking specifically for the new digital works, and of course they recognized them immediately. But in recent years, there has obviously been another enormous development.

Totally.

Apparently, many photographers started to shoot professionally digitally at a time when improved print techniques were developed, with which the result then strongly co-incided.

Absolutely, yes.

Your position has become clear: For you, it is about a museum or an institution that researches this medium. But that brings up the next question: What kind of photography does an institute like this cover? Does it have to be about the medium in general? Or does it only look at artistic photography? Does it have to go wide or does it have to specialize?

I believe that in every branch of photography there are results that are worth saving. Martin [Kippenberger], for example, loved a photographer I didn’t even know, he was a toe fetishist, Elmer Batters. It was completely crazy what this person did, but also really interesting! Well, and there are certainly pornographic images that are great. I really wouldn’t make a distinction now whether it’s art or not. I would just look at what the quality of the material is. I’ve been on many juries, and I’ve seen that the decision there was made according to what was fashionable at the time. After all, that can’t be it. We have to choose what goes a little bit beyond that line. Back then in the juries, I often thought that while I think craftsmanship is important, if you let me choose between two photographs, and of the two, one is perfect and the other one is not, but with a content and direction that inspires and makes you happy, then I don’t care about the technique and choose the imperfect photograph. If the technique serves no purpose, meaning no content, no thought, then I don’t give a damn. Sometimes you have to let yourself be redeemed by something that goes a bit further than what you thought was possible and good.

If you now imagine that there was such an institute and all your criteria were met: On the one hand, that pictorial quality is decisive and not technical perfection, and on the other hand, that photographers from very different contexts can come together here – who chooses?

Yes, who chooses? That is the eternal question, the outcome of which we cannot decide, cannot determine. It always depends on who is in power. Here in Austria, we have chancellor Kurz9, yes, what will it look like?! It’s simply a question of how much integrity people have. Because all these questions are closely entangled with politics. That is the most sensitive question. The bigger such an institute is, the better it seems to me, because then simply many qualified people come together who have to exchange ideas. In Austria, I already know some people who would like to see such an institute or museum. But I am not sure if this is a direction that interests me. On the other hand, it doesn’t have to be about my interests.